The Rhythm of Centers: Patterns of the Human Habitat

Based on a presentation given at CNU 25, Seattle, Washington

Just as one may study animal habitats to learn about how a particular species lives and interacts with its environment, an examination of the built environment might similarly help us understand the way in which humans interact with the world around them. A close study of human settlements reveal the rhythms and patterns of human habitation. Walkable urban places are a physical manifestation of these patterns and define the human scale.

Cities are essentially an assemblage of centers. A center is a point at which there is a convergence of human activity. They tend to be home to a concentration of shops, restaurants, bars, and also civic or religious institutions. However, centers can also be small urban moments, such as those situated around monuments or fountains. Where centers occur can be based on a variety of factors; however, a natural rhythm of centers typically emerges, and is based fundamentally on the time it takes to walk from one to the next; hence, the human scale.

For years, the rule of thumb to scale walkable urbanism has been the 10-minute walk or 1/2-mile—describing the approximate distance that one can comfortably walk to reach their destination. As such, the ideal scale of a neighborhood can be illustrated by drawing a circle of that diameter (where the neighborhood center falls roughly in the center of the circle). Furthermore, once assembled in the multi-centric city, neighborhood centers would also fall approximately 1/2-mile, or a 10-minute walk, from one another. And very often, this is the interval of transit stops as well.

What I would like to propose is that understanding the true

pedestrian scale requires a more nuanced approach. There is overwhelming evidence that it is in

fact 660 feet, or 1/8-mile, a unit known as the furlong, which defines the

human scale. It is what I would like to

call the urban unit of measurement. The furlong, or about a 2.5-minute walk, is

the optimal distance between centers because it also defines one’s immediate experiential vicinity. The 10-minute walking circle describes the

distance that one can comfortably walk, but the furlong describes the distance

that one can easily experience.

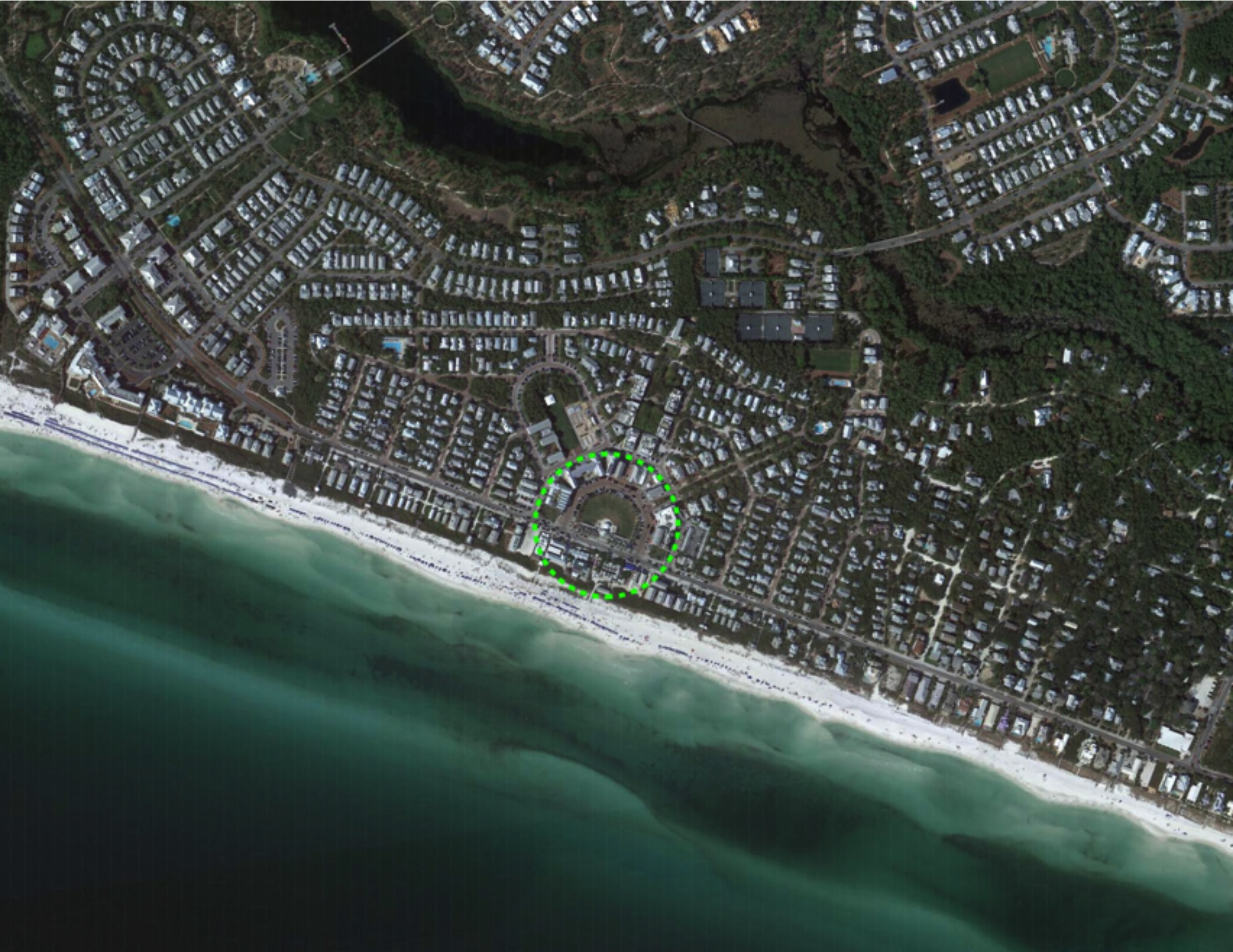

You can begin to identify this pattern by starting small, and examining the village—small urban settlements with a single center. In the following examples, the furlong consistently stands out as the ideal scale of the commercial core. That is, the commercial zone of the village will fit into a 660-foot diameter circle.

Next, consider a few of the most well-known public spaces in the world and how they too are controlled by the furlong. Good urban spaces should be contained within this 660-foot dimension in order to be properly scaled and experienced.

For cities that developed pre-automobile and pre-mass transportation, centers most often grow in the rhythm of the furlong. And if you accept the notion that the furlong defines the immediate experiential vicinity, you can see that in mature urban environments, a center is usually located somewhere within this dimension—such as the below diagram of the Medieval core of Bruges, Belgium, illustrating the arrangement of some of the city’s centers and urban moments.

Even in planned

pre-automobile cities, this rhythm is present.

Savannah, Georgia’s clear diagram of the Ward, focused around a central

square and distributed on a rational grid, relies too on the scalar

organization of the furlong.

In the “modern” American city, the distribution of activity and commerce tends to coincide closely with transportation thoroughfares. Therefore, whereas the European center is typically located around a square, plaza or some type of centralized public space, the American center tends to be a linear space. Think of the quintessential American Main Street.

In Brooklyn, New York, similar to many American cities, the furlong curiously shows up as the approximate dimension of the long side of the blocks. However, what is missing here are centralized spaces and urban moments that add interest and hierarchy to the city. Activity is instead concentrated along linear corridors—emphasizing a relentless movement. Centralized spaces provide a pause, which together with commercial streets, create a rhythm that makes it more enjoyable to walk (and propel the pedestrian to walk further). In this part of Brooklyn, the only centralized space that occurs is over-scaled and more vehicular than pedestrian in nature.

A glance back at Bruges (shown at the same scale) provides a convincing example of a commercial spine, which connects a series of centralized public spaces, in the rhythm of the furlong.

In the Columbia Heights area of Washington DC, commercial corridors follow a pattern similar to Brooklyn, in that they are located about 2 furlongs apart; they are also linear in nature and generally lack the richness and rhythm provided by centralized spaces. In the 1990s, an expansion of the city’s Metro rail line was planned to run through this neighborhood, and the location of the stop was negotiated to be sited on the most primary of these commercial streets—a move that in fact instrumentally set this site up for one of Washington’s most successful neighborhood revitalizations and transit-oriented developments.

Torti Gallas played a key role in the reimagining of this site, much of which was destroyed during the riots of 1968. The master plan included, essentially, two public spaces, or centers—one at the Metro stop and a true piazza, the new heart of Columbia Heights, just to the north. The spacing of these two moments: one furlong.

As designers, it is important to think about how we begin to carve these types of spaces out of our cities, because it will enliven them with their rhythm of movement and pause, and ultimately create more pedestrian-oriented environments. Furthermore, this concept is just as important, if not more so, when considering the design of new towns, as it is an opportunity to get it right from the beginning.

The furlong has consistently proven to provide the best tool for producing walkable urbanism and achieving the true human scale. It is ingrained in the patterns of the human habitat. So, 660 feet is a dimension to always remember.